My freshman year at Yale, I enrolled in an introductory Art History lecture that ended up in the news. It was a phenomenally taught survey of art from Renaissance to contemporary that altered the way I would look at art for the rest of my life – and that semester was the last time it would ever be taught at Yale.

The department made the decision to replace a singular survey course for a variety of introductory courses with the intent of diversifying the artistic canon taught in the entry level classroom.1 Whether people applauded or reproached the decision, there was a thorough conversation about the virtues and demerits of the artistic canon that has been filtered through a mostly white, male lens.

While I find myself agreeing with elements of each argument, my own experience in the class was so extraordinary that it left me disappointed that students in the years to come won’t be able to experience the in-depth dive of Western art history that almost had me changing my major to pursue studying it more.

I could write pages on the many lessons I gleaned from that class, but one moment has been coming back to me since my trip to DC last week. On Wednesday, I found myself in the National Gallery of Art looking at a Mark Rothko painting and – to my disbelief – enjoying it.

To understand my bewilderment, we have to go back to the spring of 2020 – no, not because of the pandemic, but because I was in a lecture hall with Tim Barringer speaking and a Rothko painting projected on the screen.

We were in the contemporary art unit, and I found myself taking notes half heartedly and feeling rather unmoved by the art on the slides. This was compared to the shock and wonder I felt at the Baroque and Rococo paintings that left me leaning in and squinting from my seat to try and pick up more details. I knew after that class that I had a tendency towards paintings that were a feast for the eye and mind. I loved a luxury of details, colors, and meaning.

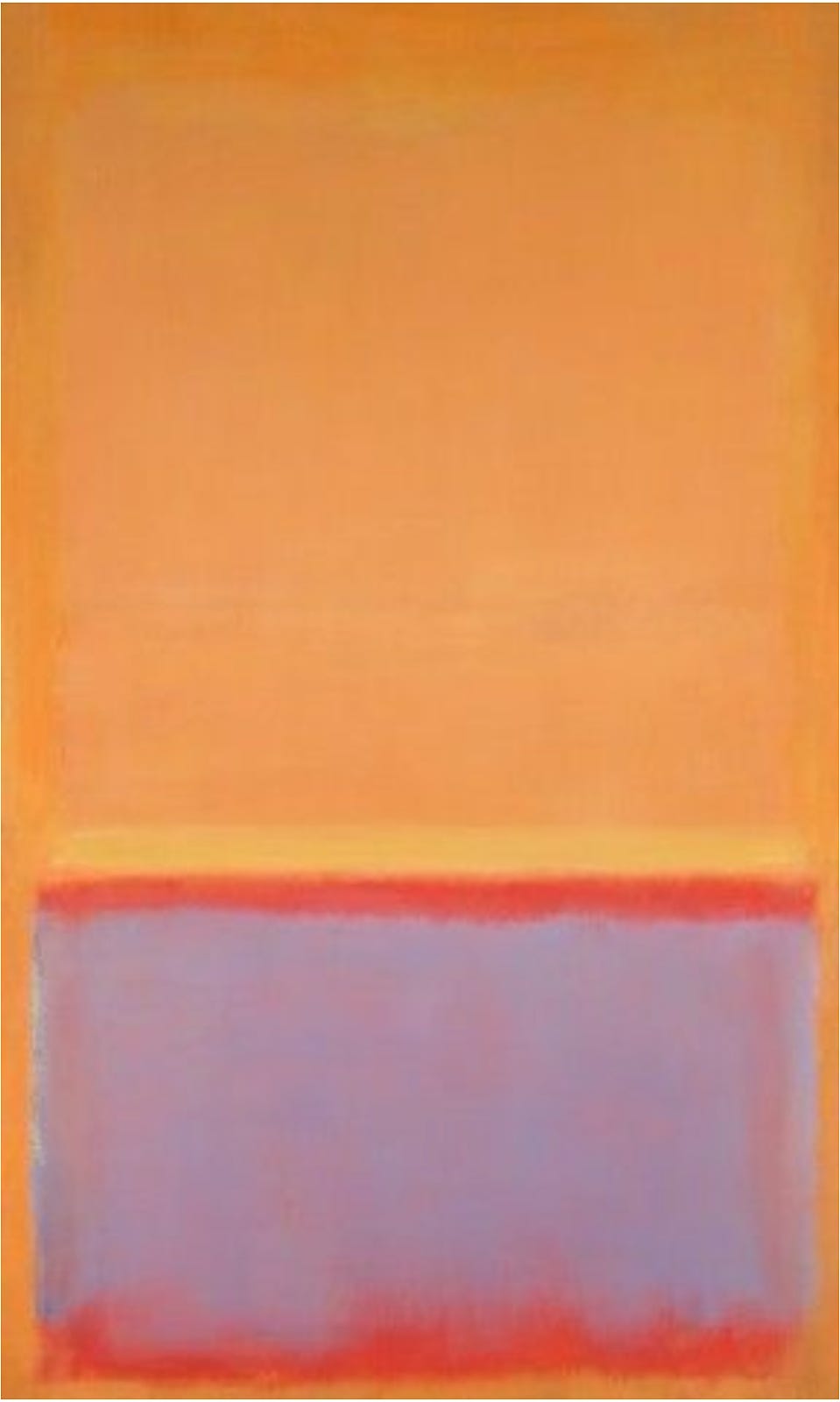

Which is why Rothko’s Untitled, 1954 left me unimpressed, and mentally quoting the old refrain, “I’m pretty sure a five year old could have painted that.” Seeing it later in person at the Yale University Art Gallery only solidified my opinion.

As my professor explained Rothko’s technique of conveying emotion rather than narrative, and how each painting was meant to be viewed up close, in dim light, I remember him saying, “Some people think Rothko is a genius, others think his paintings are overrated. Whatever the case, you either love him, or you hate him.”

He left his own perspective mysteriously unstated, but I found myself nodding along to his commentary and writing down in my notes: Rothko – not a fan. From my perspective, Rothko’s paintings represented all of the failings that came with a contemporary art movement that had little regard for storytelling traditions of art and techniques of the past. Had we fallen so far that the beautiful compositions of the Pre-Raphaelite movement had been replaced with squares of paint? I had cast my lot, and it was not with the contemporary crowd.

From then on, whenever I visited an art gallery or museum, I found myself inexplicably veering around exhibit halls that had the word contemporary in their title.

At the grand age of 19, I had established a core part of my identity in that class: a love of art, and a contempt for Rothko.

Of course, as with any decision made in young adulthood, it only took a small dose of time for it to become tempered. The moment I realized my change in opinion, however, I was left not only pondering my change in aesthetic enjoyment, but in my nature as a person.

First-year Lily was a child playing the game of academia – she was self-determined, self-defined, and in every way a girl boss. No doubt she would have sat in a 300 person lecture, taken a look at a whole genre of paintings, and decided yeah, she could do better. She held onto her opinions like shards of glass, not knowing the harder she grasped the more she cut through herself.

A lot has happened since then. That Lily survived a pandemic. She finished college despite her frustrations. And she found God in the midst of it all. This Lily looks back on her with a distant fondness and sadness for all the strife she had to experience just to realize that her hopes were only going to disappoint. We are somehow the same, but distinct. I’m grateful to have come from her naivety and blind passion that time has graciously tempered into some sort of wisdom and joy.

When I looked at that Rothko painting in the National Art Gallery, I could see the definition of colors in the dim light. What seemed like orange suddenly had more depth to it. Orange within orange, pink within pink, blue within blue. I can recall Professor Barringer saying that Rothko painted one thin layer over another to create complex colors. I can imagine that took time.

I want to put into words the way liking Rothko represents my changing as a person — but I find that I can’t. And maybe that’s the point.

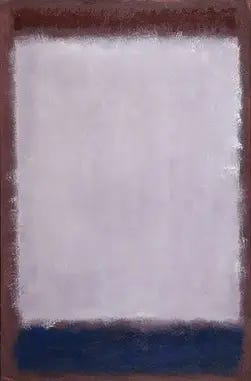

Here is a selection of Rothko’s works that I find move me the most:

Rothko’s earlier works before his distinctive style:

Works in Rothko’s established style: