booknote – Woolgathering by Patti Smith

A book review about floating down stairs, the things we forget, and the magic of childhood

As a child, I was intensely obsessed with Kiki’s Delivery Service. My mother had picked up a VHS tape of it from a clearance bin at HEB when I was five years-old, and it quickly became a staple in for understanding the world through my child eyes.

I didn’t know that Studio Ghibli, the animation studio that made Kiki’s, had other films in the same distinct style until I was on the brink of self-proclaiming my aging out of childhood. Then, I was introduced to the magic of Ponyo and Arrietty and I was pulled back and captivated once again by surreal scenes of ocean and city and wilderness.

But my fixation on Kiki’s came down to a key detail: the way life was animated on screen captured the way I understood my own experienced life. People online have pointed out the magic of Ghibli tears and liquids that seem to operate within their own laws of physics. While incompatible with the physical reality of our own world, the imagery of Ghibli captures the essence of our lived reality – a truth anchored on experience rather than fact.

In a similar but distinct way, Woolgathering captures this essence of a nostalgic Americana childhood, challenging us in the task of where we draw the line between fantasy and reality.

I picked this small book (a hanuman book - 4x3 inches) from the poetry section of my local library, intrigued when a thumb-flip through revealed mostly prose instead of stanzas.

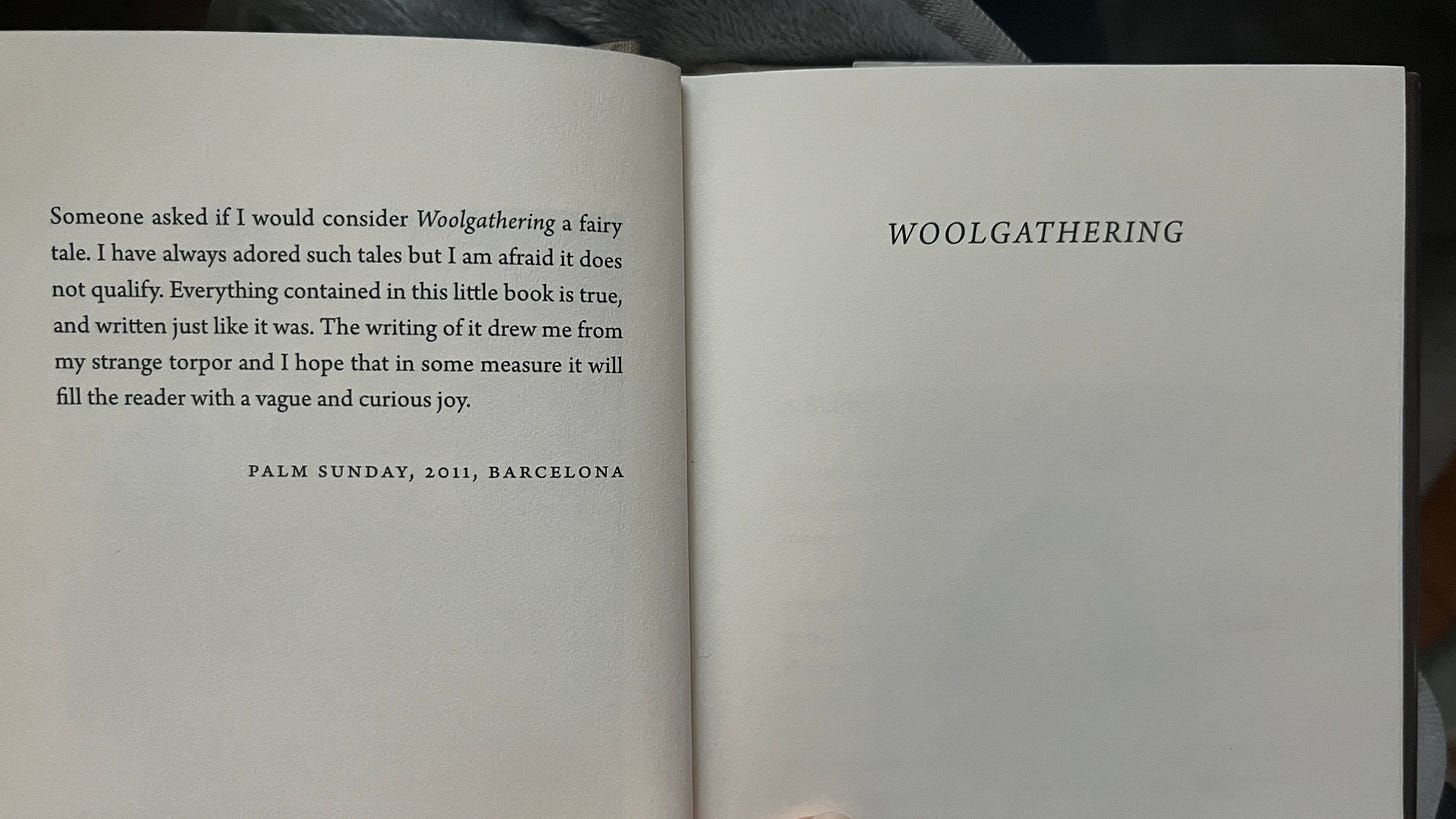

In her note to the reader, Smith concludes her introduction with this paragraph:

“Someone asked if I would consider Woolgathering a fairy tale. I have always adored such tales but I am afraid it does not qualify. Everything contained in this little book is true, and written just like it was. The writing of it drew me from my strange torpor and I hope that in some measure it will fill the reader with a vague and curious joy.”

Prepared with this clarifying bit of guidance from Smith and knowledge of its shelf home in my library, I approached this book with an open-minded curiosity as to what it might contain.

And I was not disappointed. Smith was exact in her description of the tales contained in Woolgathering.

Each chapter a vignette of a particular recollection of her childhood, Smith brings us along in her recollection of how little children are quick to see the truth of their lived reality. To adults, facts flatten the surreality of truth; to children, truth alone is sufficient.

Smith toggles between the surreal memories of her childhood in the rural 50s and the moments in her adulthood that force her to view the world with the same satisfied eyes that children have yet to see with.

I was intensely comforted by both the content and stunning cover of this book. While reading, I was abruptly reminded of the inexplicable memories of my own adolescence, the magic that had yet to be explained away by a parent eating cookies and leaving gifts, or the grown hands exchanging the baby tooth for a dollar bill.

Madeleine L’Engle in her book Walking on Water recounts the memory of once being able to fly down the stairs as a child.

“I used to go down the winding stairs without touching them. This was a special joy to me. I think I went up the regular way, but I came down without touching. Perhaps it was because I was so used to thinking things over in solitude that it never occurred to me to tell anybody about this marvellous thing, and because I never told it, nobody told me it was impossible.”

This asserts a particular certainty that we as children have about the inexplicable. With no need for explanations, we live in each moment unaware until told by others that we are experiencing magic – and that, of course, makes it impossible.

When presented with the impossibility of truth, we are inevitably forced into the corner of factuality by the world around us. L’Engle’s own ability becomes grounded after a few years spent abroad for the care of her sickly father.

“When I was twelve we went to Europe to live, hoping the air of the Alps might help my father's lungs. I was fourteen when we returned, and went to stay with my grandmother at the beach. The first thing I did when I found myself alone was to go to the top of the stairs. And I could no longer go down them without touching. I had forgotten how.”

What both L’Engle and Smith get to in their vignettes is how childhood becomes interrupted by reality. And once interrupted, these memories of surreal truths become forgotten from misuse.

In her poetic language, Smith invites us to remember these times through the experience of her own impossibilities. From her own ability to fly over night shrouded fields, her glittering ruby once misplaced that has been found in scarlet drops all over the world, to the clouds she once conversed with to the unawares of her siblings and friends.

As Smith concludes her book, she presents the power of recalling childhood as truthful and how it can allow us to embrace the surreality of our own lives.

“And these words of advice, imparted with such undivided grace, filled my limbs with such a lightness that I was lifted and left to glide above the grass, although it appeared to all that I was still among them, wrapped in human tasks, with both feet on the ground.”